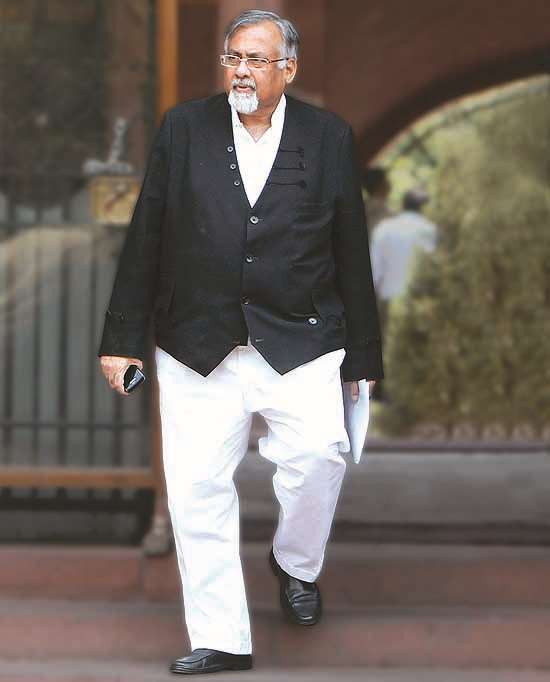

UTTAM SENGUPTA : Outlook :Nov 18,2013

Goolam Essaji Vahanvati, the Attorney-General of India,

courts more controversies than he helps dispel

courts more controversies than he helps dispel

Things have come to such a pass that every move Goolam Essaji Vahanvati, the Attorney-General of India, makes ends up fuelling further speculation about his future. Three weeks ago, the close-knit community in Delhi’s Supreme Court was all aflutter when the normally reserved Vahanvati greeted lawyers and court reporters with big smiles, handshakes, and even a bit of chit-chat. Only the previous month, he had uncharacteristically lost his cool in the apex court, complaining “I cannot carry everything in my head” and saying that he was being asked too many questions, and too fast.

Vahanvati quickly tendered an apology at the next hearing. But clearly, something is getting to the 64-year-old attorney-general—a much-observed and talked-about man, unlike most law officers of the government, past or present. That’s because questions are being openly asked whether the country is getting adequate and sound legal advice; as the country’s top legal officer, providing that is Vahanvati’s job. As an embattled UPA struggles with many demons of its own making—from 2G and Coalgate to the validity of opinion polls and the question of the functional ambit and autonomy of the CBI—Vahanvati has a stake in each and every one of them.

The past few years have been a public relations disaster for a man who had in a recent magazine profile reportedly confided that he had in his childhood dreamt of being driven around in an official car with a red beacon (and so he does, with a ‘fancy’ number—777—to boot). Partial to Vahanvati, former A-G Soli Sorabjee told Outlook, “I know Goolam. He has gone through hell.” Sorabjee should know how tough it is to be the A-G. He occupied the office in 2000, and fought a bruising battle with the then law minister Ram Jethmalani. Sorabjee won that round, as Jethmalani was made to resign.

|

The A-G is not just a lawyer and the first law officer of the government, he is appointed by the President under Article 76 of the Constitution, remains in office till the pleasure of the President and draws a remuneration decided by the President. While he is expected to give legal opinion to the government as and when it seeks any, he is also expected to advise the government in upholding the rule of law. He is a leader of the Bar and must necessarily be eligible to become a judge of the SC. He is expected to assist the court in delivering justice.

It is in this capacity that the A-G is seen as a “friend of the court”, the government’s “conscience-keeper” and the legal custodian of the interests of 1.2 billion Indians. Legal eagles Outlook spoke to recalled the deposition of the first A-G of India, M.C. Setalvad, before the M.C. Chagla Commission of Inquiry against the then finance minister T.T. Krishnamachari. Setalvad’s scathing indictment of the minister led to his resignation in 1958. And though Congress MPs then raised questions about how the A-G actually turned out to be the prosecutor, Setalvad stayed on in his post till 1963.

.jpg.ashx?quality=40&width=550)

But times have clearly changed. Vahanvati, the 13th A-G, is seen more as a facilitator for the government, tailoring his legal opinion and advice to suit the political establishment, crony capitalists and politicians. He has been described as the government’s ‘hit man’ (by top SC lawyer Rajeev Dhavan in Mail Today), provoking a veteran SC observer to quip that all A-Gs are “by definition hit men while some turned out to be even the henchmen of the government”.

A section of Delhi’s political grapevine attributes Vahanvati’s survival to the patronage he enjoys from 10, Janpath, and more specifically from everyone’s Ahmedbhai, Sonia Gandhi’s political secretary Ahmed Patel. Others speak of his proximity to Maharashtra politicians Sharad Pawar and Sushilkumar Shinde while everyone agrees that he has the backing of the who’s who of the industrial lobby in Mumbai, like the Ambanis, Ruias, Tata and Vedanta. His alleged friendship with Anil Ambani has often cast a cloud over his professional conduct.

|

Unlike his predecessors, he is also not seen keeping the political establishment at arm’s length. Consider his complaint about receiving a phone call in September from a woman who allegedly pretended to be UPA chairperson Sonia Gandhi. Media reports suggested that Vahanvati checked with UPA leaders and when informed that Sonia had not called him, lodged a complaint with Delhi Police. Curiously, the police initially claimed to have tracked down the caller and identified the lady as an officer working for a public sector undertaking. But thereafter not a whisper has been heard about the case.

“I do not know what wrong I committed in my last life that the media is after me,” Vahanvati said in court in 2011. But it is a tribute to his quiet networking skills and his friendship with media barons that the media has by and large left him alone. Indeed, Vahanvati has survived one controversy after another. To put this in perspective, there have been four Union law ministers since 2009, the term of each one shorter than his predecessor. M. Veerappa Moily lasted a little more than two years. Salman Khurshid a little more than one, Ashwani Kumar less than one while the present incumbent Kapil Sibal took over in May 2013 and, if not replaced, will also have a tenure of less than a year.

During this same period, two eminent lawyers—Gopal Subramaniam and Rohinton Nariman—also put in their papers as solicitors-general of India, apparently because they did not see eye to eye with Vahanvati. One of the additional solicitors- general, Harin Raval, resigned after accusing the A-G of compromising his position in court; another additional solicitor-general, Bishwajit Bhattacharya, released a book the day after demitting office on November 9, 2012, to give vent to his frustration. During his three-year tenure beginning 2009, wrote Bhattacharya, the A-G did not call a single meeting of all law officers together. Bhattacharya often received briefs late at night for cases to be argued the next morning in the SC.

What say? Vahanvati with Salman Khurshid, R. Chandrasekhar. (Photograph by Jitender Gupta)

Amidst such bloodletting, the one constant has been the A-G himself. Curiously, the apex court has been rather lenient to him. Consider Coalgate. Since the CBI has been investigating the role of government officials and politicians and possible criminality, the A-G—as the lawyer of the government—had no business interacting with the investigating and the prosecuting agency. But that’s exactly what he did. Even when an affidavit by the CBI director revealed that Vahanvati had misled the court, he was let off with the mildest of rebukes by the court as well as the government whereas Raval and law minister Kumar were forced to quit. Could it be because he has been defending the prime minister, who was directly in charge of the coal ministry? Is it because he knows too much?

|

After the Supreme Court cleared the deal and then FM Pranab Mukherjee brought in a retrospective amendment in the rules to address cases like this, Vodafone approached the government for conciliation and an out-of-court settlement. At this time, Vahanvati advised then law minister Kumar to deny conciliation. But soon after, Sibal took over as the law minister and sought fresh opinion from the A-G, he took a U-turn and advised him in favour of conciliation.

Vahanvati himself is not unduly perturbed by charges of flip-flop. “On numerous occasions,” he told The Times of India, “after the opinions are rendered, I receive requests to reconsider or review the opinion. This is sometimes based on additional facts or on some provisions of law or the Constitution not previously considered. This could lead to reiteration or reconsideration of the opinion....”

For instance, the Public Accounts Committee summoned Vahanvati to explain his conflicting opinions on the CAG’s contention that the government had withdrawn Rs 37,365 crore from the Consolidated Fund of India without Parliament’s approval in the past five years. Vahanvati first advised the PAC the CAG’s stand was correct. But when the finance ministry called for a fresh opinion, he concurred and held that Parliament’s approval wasn’t required as interest payment on I-T refunds was both a statutory and recurrent obligation.

His opinions have been so controversial that a plea was made under the RTI Act to make the A-G’s opinions public. But the A-G pleaded that he was not a public authority. Chief Information Commissioner Satyanand Mishra upheld his plea that the A-G was a “single entity”, did not have a secretariat unlike other constitutional functionaries and that his relationship with the government was that of a lawyer and client and not of servant and master. The cic also accepted the plea that the A-G had no administrative control over other law officers. The undefined role and position of the A-G, whose advice is not binding on the government, was further accentuated when former Union law minister Khurshid was quoted as saying, “The attorney-general is an officer of the court and not an officer of the government.”

|

With as much as 80 per cent of the SC’s workload comprising Special Leave Petitions involving civil or commercial disputes, and the bulk of the cases emanating from just four or five high courts (Delhi, Bombay, Madras, Punjab & Haryana and Allahabad), the possibility of conflicts of interest clouding the judgement of a corporate lawyer is clearly high. Vahanvati, like those belonging to similar lawyer families, faces the same allegations.

That said, people who have known Vahanvati are effusive in hailing him as a genius who has a ready solution to every problem. Above all, he is credited with having a sharp legal mind. He was the first Indian lawyer who was allowed to argue a case in London in the early 1980s. “A man of great integrity” is what eminent jurist Fali Nariman had said when Vahanvati was appointed.

By all accounts, Vahanvati is a likeable man with varied interests. He likes rock music and is a gardening enthusiast. Vahanvati is said to know the names and details of every plant brought in from all over the world in his four-acre farmhouse in Pune. He bred horses but following the death of his favourite horse, he reportedly gifted all the 17 horses he had to his friends “free of cost”. He lectured at St Xavier’s College and Sophia College, Mumbai, and wrote on history of food in the inhouse magazine of Taj. He also wrote a weekly newspaper column on legal affairs for four years.

His acquaintances too are fulsome in their endorsement of him. “Diligent”, “obsessive about details”, “relentless”, “generous”, “very sweet” and much “understated” are some of the adjectives used to describe Vahanvati. He is also said to be a “great raconteur”. A perceptive profile in Caravan, however, brought out a disconcerting detail. Vahanvati claimed that when his father died, he did not even have the resources to bury his body. He also claimed that he had no fascination for fancy stuff and pointed to an array of modest pens on the table. But Vahanvati’s son later told the interviewer that his father had one of the most extensive collection of expensive pens at his farmhouse.

Why would the A-G be so economical with the truth on such a petty issue?

There is no clear answer.

In a rare interview he gave to Misbah, a Dawoodi Bohra journal, after becoming the A-G, Vahanvati had spelled out his ambition. “I want to go down in history as the first attorney-general who really tackled the problem of judicial reforms.” But obviously Vahanvati has not been able to do so, pleading that he has become far too busy fighting legal battles for his masters. His critics and well-wishers are, however, left wondering whether he has served the country equally well.